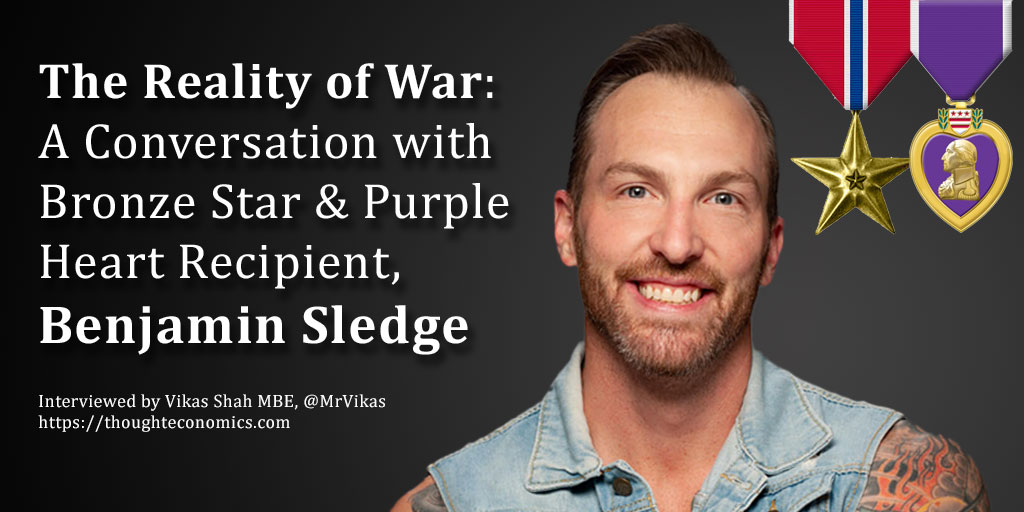

Benjamin Sledge is a wounded combat veteran with tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, serving most of his time under Special Operations (Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command). He is the recipient of the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and two Army Commendation Medals for his actions overseas. He was at the front line of some of the deadliest battles in Iraq and Afghanistan, served in Special Operations Command, on the Pakistan border after September 11, and eventually in the deadliest city battle of the Iraq War, Ramadi.

Haunted by his experiences overseas, Benjamin began a 15-year odyssey wrestling with mental health, purpose, and faith. He notes that Hollywood wants to sell us jingoistic heroism despite men and women being crushed under the weight of 20 years of war with no draft. Many soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines came home institutionalized, war sick, and wondering how to readjust and in his new book, Where Cowards Go To Die, Benjamin Sledge vividly captures the reality of the men and women who learn to fight without remorse, love each other without restraint, and suffer the high cost of returning to a country that no longer feels like home. But war never leaves its participants unscathed. Sledge reveals an unflinchingly honest portrait of war that few dare to tell.

In this interview, I speak to Benjamin Sledge about the realities of war, how soldiers prepare for combat and what war reveals about the best, and worst of humanity.

Q: What do you wish people really knew about war?

[Benjamin Sledge]: My grandfather was a paratrooper in World War II, he taught in Europe. He missed the D-Day jump because he had pneumonia! From there, he was transferred to Germany with Patton’s 3rd ID. When he came home, he never really talked about his experiences except for being General Patton’s Scotch supplier!

I think we have this weird, nostalgic, romanticism about combat – but the reality is, you’re dealing with death, destruction, and collateral damage. My grandfather and his generation were told this was their finest hour, and it’s strange isn’t it… some of our finest hours are the most heartbreaking. In war, you watch your friends die, you are forced to take a life and protect life, and that reality is often played back to you as a soldier as being part of your finest hour. Those are the endless terrors that play back to you for the rest of your life. There’s a real disconnect, war is glamorised, that’s just not the reality.

Q: Did your training really prepare you for combat?

[Benjamin Sledge]: In army training, you take an 18-year-old kid, shave his head, take all his clothes away, issue him with new ones, and now he looks like everyone else. You then begin to train him in how to fight enemies in combat. You train him how to dehumanise the enemy- they become pop-up targets. We’ve seen through history that soldiers use dehumanising slang terms for their enemies; the Germans were called the Krauts, the Japanese were called the Nips, you saw the Charlies & Gooks in Vietnam, and in the more recent conflict, you saw the term Hajji used to describe the enemy in Afghanistan and Iraq. The term Hajji is an Islamic term of endearment for somebody who made the Hajj to Mecca, but we turned it into a dehumanising slur in combat. So, you give this kid a new identity, a rifle, and convince him that death on the battlefield is glorious. Throughout that process, you are training them to kill or be killed.

Every soldier who enters the military knows what makes the grass grow. Civilians are like, ‘okay… sun? Water? Photosynthesis?…’ for us? Its blood, we say the bright red blood makes the green grass grow.

In military training, you go through a process where you’re stripped of your old identity and reformed into one where you become a conscious killer. If you hesitate in combat, you die. You can’t have hesitation otherwise you’re going to die on the battlefield. In training, you must develop that muscle memory to not hesitate.

Nothing prepares you for the experience of real combat though.

Soldiers don’t get post-traumatic stress on the battlefield, they get it when they get return. When you’re there, on the battlefield, life is simple. You have a mission, a purpose, a direction, and you’re trying to survive. It makes for a grand, exciting life. You know that any moment, you could die, but you live through this thing. When you come home, that’s when you have to reconcile your humanity with who you are, and what you were forced to do. That becomes a problem for many of us. I faced into this twice, coming home from Afghanistan once and then Iraq the other time.

Q: What did war teach you about the darker aspects of our humanity?

[Benjamin Sledge]: Philosophers have often spoken about our shadow self, the side of us we don’t want to admit. If we were able to walk around with projectors on our foreheads, we’d think we were all monsters. We all have thoughts day to day which sometimes appalls us. Those are the thoughts which make us think where did that come from?.

In war, you’re forced to survive. It’s kill or be killed, it’s the most basic human instinct. You have to unleash that aggressive shadow side of yourself. It gives you a profound sense of being alive, it becomes a dopamine slot machine. That’s why so many soldiers get institutionalised to war. They go so often that the environment becomes comfortable, and home becomes alien. If they committed the acts in civilian society, that they commit on the battlefield? They’d land in jail. That’s the danger when the shadow side takes over.

Q: How did you rediscover a sense of purpose after going to war?

[Benjamin Sledge]: Readjusting after the war was hard. You have this mission, purpose, and direction but you also have this intense brotherhood, sisterhood and camaraderie. People are literally willing to die for you, and you for them. Right now, we’re going through the longest-running wars in the history of the west. All these soldiers have been engaged in long wars where one-minute crowds are trying to kill you, and then the next minute you’re back home, and it’s pumpkin-spiced latte season and nobody cares about you because they’re weary of hearing about war. Sometimes you come back to an environment that feels ungrateful, even though in reality people do appreciate your service. You come back and go to a job where your boss is trying to make an extra buck and your co-workers are trying to trample each other to get ahead- even though you just came back from a place where people were willing to die for you, and there was a profound sense of having each other’s back. It’s very jarring. You suddenly lose that camaraderie, purpose and direction.

A 2012 study showed that where veterans did not find a new sense of purpose, direction or community (whether that be sports, faith or so forth), they continued to struggle for the rest of their lives.

When I came home, I had two civilians who made sure that I came home from war mentally as well as physically. They helped me to open up, find a new purpose and find a new direction. They showed me that life isn’t that awful and helped me find my next step. I found my new unit, and that gave me a profound sense of purpose and meaning.

Q: How did you heal from seeing so much death?

[Benjamin Sledge]: I don’t honestly think I’ve healed from that aspect of my journey; even now, when I hear about someone who died, I’m like, ‘oh well, death is normal, we all die…’ – most people die like their pets, they’re not going out in a violent manner, where their body is being ripped apart and they’re crying out for their mom. Most people are dying in hospital beds, and for the most part, comfortably. Death in combat is uncomfortable and brutal. You become desensitised to the whole process and you realise that everyone is a car wreck, bullet or cancer diagnosis away from taking a dirt nap. It sounds terrible, but you do get numb to death, and it makes it seem kind of’ trivial. It’s a very strange feeling where you just become okay with this notion of dying.

Q: Did your time in combat change your understanding of sacrifice?

[Benjamin Sledge]: My best friend was killed while we were in Afghanistan. He came to replace me and died a week later. I still deal with that every day. He was a journalist- that’s what he wanted to be in life. He covered everything from investigative journalism through to the miss universe pageant (which he covered just before coming out to Afghanistan). He bought this ugly fresco of Panama and gave it to my mom. He said, ‘you have to put this in a place where everybody can see it!’ she was like, ‘Kyle! It’s ugly, why would I ever do that?’ – Now, it’s a ghost that haunts our house. Every time we pass it… there’s Kyle

Kyle was like my mom’s other child; he had a key to our house. When I was gone in Afghanistan, he came over to check on my parents. It still stings now… and I still have the survivor’s guilt which says, ‘it should have been me…’ – when you die in combat, you die twice. You’ve given up the life you had, and the life you were going to have. It’s profound and heroic. That’s sacrifice.

Behind me, I have my Purple Heart, received for wounds In action. The original medal, I have to Kyle’s dad. I didn’t feel worthy of receiving it when I had lived, and he had died. Napoleon once remarked that it was amazing what men would do for a piece of ribbon – and he’s right, these military decorations are just a ribbon or a ribbon with a piece of metal, but they have a weight to them – a profundity. For those of us who receive these awards, we do feel undeserving, when those around us gave everything.

Q: What has been the role of faith in your life?

[Benjamin Sledge]: I grew up in Oklahoma, in the buckle of the Bible Belt in the 1980s. It was a very weird time when the prosperity gospel was doing the rounds. The principle is that if you have enough faith, Jesus will grant you a Maserati and a mansion! It was very intermingled with politics. My upbringing was very similar to the movie Footloose with Kevin Bacon. I couldn’t dance, drink, date, or any of that stuff – it was deeply masked with morality. You then saw all these scandals in the churches, it was like rules for thee, none for me. Pastors were caught sleeping with their secretaries and embezzling funds, of all sorts. By the time I was 17, I thought this stuff was all bunk, and I took that Karl Marx methodology where I assumed it was all an opiate to control the masses. I didn’t tell anybody, I didn’t’ want the scary, ‘you’re going to burn in hell’ talk, but I just wanted to continue to do my own thing. Then I went to Afghanistan and Iraq. Those tours really made me wrestle with the question of what matters, and what values are. If we think about it – as humans, we’re awesome at killing each other… we think we’re so noble in the modern era, we think we’re not as barbaric, but in the meantime, we have built weapons that can literally destroy the world and automated drones that can kill people. It’s never been easier, or more efficient, to kill people and commit mass atrocities. So how can we assert to be enlightened?

I read so much philosophy from different places, and different religions, but I didn’t find a way of tackling these existential, questions till I got home. People deny the fact that war is a spiritual experience. Think about it – most of us believe we know what will happen when we die, that may be heaven, it may be reincarnation, it may be nothing. We all think we know, but there’s no real consensus. It’s unknown. If you point a rifle at a man and pull the trigger, you’re going to send them to that unknown, and there’s something deeply spiritual about that, it’s like you’re playing God. You have the power to protect life or take it away. I had to wrestle with those things.

I was in a spiral when I came home. I’d gone through a divorce, I was binge drinking, and I was miserable. One of my best friends, who’s an atheist, suggested I go to church! I went along, and I really felt that message pour into me. The two men preaching that day were phenomenal, it changed me, and I saw the work of true Christians – caring for the poor, the marginalised, the oppressed, and living the life of Jesus Christ. It was through the Church that I began to find once again meaning and direction. I wanted to live my life in the service of other people, just not on the battlefield. I found it emotionally satisfying and intellectually stimulating. That’s where I landed the plane.

Q: What did war teach you about the meaning of life?

[Benjamin Sledge]: War taught me that there’s beauty in tragedy, you just need to know where to look. As human beings, we’re so short-sighted. If you ask anyone when they grew the most in life, chances are it came from their greatest wounding, it came from those moments where they look back and say, man, I made it through that. War taught me that there’s so much to be appreciative for. I’m so appreciative of the life I live now.

When I came home from Afghanistan, I remember I literally flushed the toilet five times because I’d been out there defaulting in an oil barrel. I remember running the hot water out because I forgot how it felt to be clean. I remember when we were leaving Iraq, and stopped via Kuwait, we went to McDonald’s, and it was so funny, that one sight of McDonald’s made me realise how much of a gift we had to still be alive.

When I came home, I struggled because everything was an assault on the senses. I had a million choices and had to reconcile them with who I’d become. There was an inherent beauty though which came from the search for meaning. We are a phenomenal species, and we’re worth fighting for, and civilisation is something worth giving your life in the service of.

Social media and politics have really divided us. Instead of yelling at each other in the comments sections, we need to sit across from each other and realise how much we have in common, not what our difference are. I think a lot of the population forgets that. In war, we’re taught to give up our lives in the service of a country, even if that country may not be grateful for what we’re doing. We’re taught, in a way, to love unconditionally and fight for peoples rights even if they disagree with what we’re doing.

I remember we had the Westboro Baptist Church come to protest one of my friends who was killed in combat. I was leading the 21-gun salute and I was furious. My team sergeant looked at me and said, ‘let it go… this is exactly what we fight for… so that people can say and do dumb stuff…’ my friend Toby, who had died, would have known that, and I should have done too. I want people to have the freedom to say whatever they want. War taught me that even if people are ungrateful, I want them to enjoy their lives and know that they have these freedoms because of those who- even if they disagree- would give their life in service of them.