I’m a British Indian, but have never been too far away from my roots. From a very early age, my parents took me on the long-journey to India- not just to visit our family, but also to explore the country. They were careful to never give me a sanitised view, and as a child I bore witness to the plight of other children, like me, who faced conditions I could not even comprehend.

Viewing these situations with the idealistic naivety of a child, the fact that children were working and not at school seemed anathema, but it was only as I got older that I realised the scale of the injustice I saw.

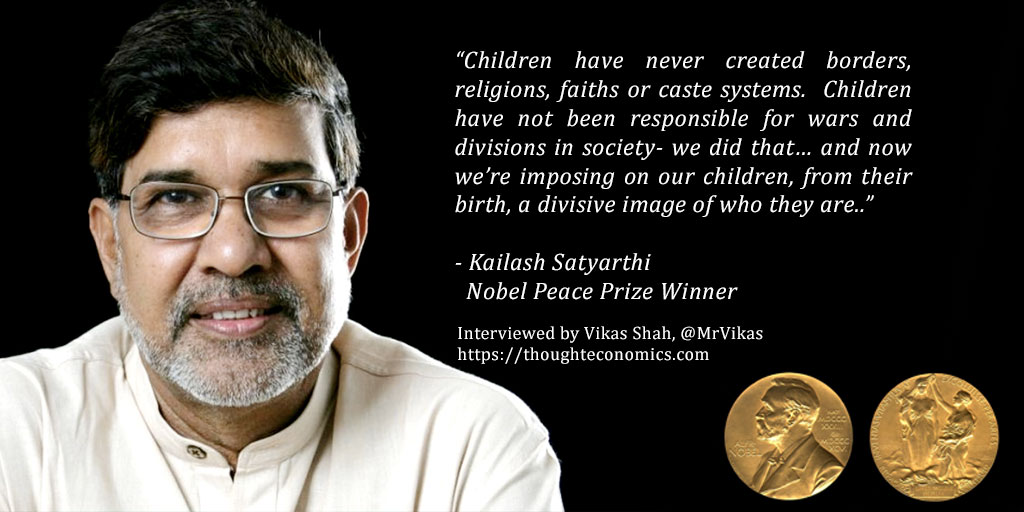

Kailash Satyarthi was jointly awarded awarded the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize for “the struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education.” He has been a tireless advocate of children’s rights for over three decades. He and the grassroot movement founded by him, Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save the Childhood Movement), have liberated more than 84,000 children from exploitation and developed a successful model for their education and rehabilitation. Mr Satyarthi has been the architect of the single largest civil society network for the most exploited children, the Global March Against Child Labour, whose mobilization of unions, civil society and most importantly, children, led to the adoption of ILO Convention 182 on the worst forms of child labour in 1999. He is also the founding president of the Global Campaign for Education, an exemplar civil society movement working to end the global education crisis and GoodWeave International for raising consumer awareness and positive action in the carpet industry.

The Plight of Hundreds of Millions of Children

“A large number of children are able to enjoy their childhood to the fullest, receive a good education, and have their health needs looked after….” Sathyarti told me, “On the other hand, hundreds of millions of children are denied of their childhood; they are living in abject poverty, and forced to live with conflict and violence. Children are bought and sold like animals, sometimes at a lower price than animals. 168 million children work as child labourers, more than 200 million children who should be in education are not at school. We see two different constituencies of children. One group who enjoys their childhood, and others who are deprived of their fundamental right to be children.”

With injustice at such an immense scale, it seems incredible that policy-makers haven’t acted, but as Satyarthi told me, “Those children who are enslaved, and victims of violence, belong to those sections of society that don’t have a strong political voice or who are taken for granted by politicians and elites. Most of those children therefore belong to marginalised and excluded sections of our society.” Critically he notes that, “The rights of children are not yet acknowledged as the key driver for human progress and development and hence they are not getting priority in economic, social or political discourse. Traditionally, children were either treated badly because they were poor and therefore could be exploited- or some people felt that children should be given ‘charity.’ The naïve engaged in charity, and others exploit them economically, physically and sexually. We have come to consider children as either being exploited or subject to charity; we hardly ever consider them as the equal human beings they are, born with certain inalienable rights. We must strengthen our notion of children’s rights within our cultures and societies.”

The Scale and Impact of Child Labour.

There are very few individuals who will not know about child labour, but also- perhaps- few who know about the scale at which it still goes on. “According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), 168 million children are working in full-time jobs…” Satyarthi told me, adding that “of those 85 million are victims of the worst-forms of child labour; they are bonded labourers, child soldiers, child prostitutes, work in hazardous occupations or are used for petty crimes”.

I remembered the shock I had experienced as a child seeing other children having to work, and as Satyarthi noted to me, “Child labour is one of the worst violations of human rights, it’s an affirmation that we don’t respect the freedom and dignity of children in our society. It’s also an utter failure of the constitutional guarantees and laws in our world.”

Without a doubt, there are unscrupulous groups who benefit economically from the scourge of child labour, but this also has a wider unexpected economic impact and as Satyarthi said to me, “Once children are employed in any area, they work at the cost of adult employment. In a world where we have 168 million full-time child labourers, we have just over 200 million adults who are jobless. Studies in India, Philippines, Nigeria and Peru have shown empirically that there is a parallel between child labour and adult unemployment- and those unemployed adults are often the parents of those children. These children often end up suffering significant mental and physical health problems as a result of their work that severely impact their lives into adulthood. Child labour is the biggest obstacle to education in our society, and we live in a world where education is the key to human progress, equity and equality in society. Education is the key to empowerment and poverty alleviation.”

Ending Child Labour

I asked Kailash about how culpable consumers are in the existence of child labour, and his answer was both a reality-check and an inspiration for action. “In our market-economy, consumers have the power.” He said, “I also believe that almost every consumer has an element of compassion in herself or himself. If they are educated and sensitised about the existence of child-labour directly, I hope they use their consumer-power and translate it into pressure and change in corporate behaviour.”

Drawing example from his own experience he noted, “I’ve seen this happen first-hand in the carpet consumers campaign. I launched the Goodweave campaign in Germany in 1990 and later on in other countries in Europe and the United States. It’s become a landmark campaign, resulting in a significant decline in child labour in South Asian carpet industries from over 1 million to less than 200,000. Consumers can pressurise the industry- exporters, importers, dealers and manufactures- and this works.”

Child labour occurs in many industries. Satyarthi told of how the chocolate industry in the Ivory Coast and Ghana was shown to be employing hundreds of thousands of children as labourers in various forms. This has resulted in the formation of the International Cocoa Initiative, where he was also a founding member.

These campaigns matter, especially in industries where the concentration of child labour is at its peak levels but as Satyarthi notes, “The garment industries are the second largest employers of children after agriculture in most countries that are producing garments, but we have no strong consumer campaigns around this.”

The Power of Education

Time and time again, we see that education is the solution to many of our world’s greatest social ills, and as Satyarthi told me, “Campaigning for children’s educational rights is one of our biggest fights.”

His campaigning has been successful, and education is now not just included as a millennium development goal, but specifically noted as being equitable, of quality and life-long. This win didn’t come lightly, and was borne out of the experiences Satyarthi’s organisations had working with hundreds of thousands of children in the field, globally.

The Wrong Priorities

“Unfortunately, neither the international community, the industrialised world nor many nations are prioritising education in their ODA (development) spending…” he told me, “The situation is that less than 4% of ODA goes to education. In most countries, less than 2% of their GDP is earmarked for education, and when it comes to humanitarian aid? Less than 2% goes to education in worldwide humanitarian assistance.”

Asking what we can do, he notes, “We need a mass movement in civil society for equitable education. The quality of education has been picked up by the World Bank and others because that guarantees them a workforce with the right skills, but quality cannot be achieved at a large scale until we make education inclusive and equitable.”

Finding Solutions

“I have more trust in youth and children than in anyone else.” Satyarthi told me, adding “I don’t want to find the solutions for children’s problems in a conventional manner through preaching, teaching and learning.”

As anyone who’s met Kailash will know, those words manifest into action. He is in the process of launching one of the largest activist campaigns humanity has ever seen, where he plans to mobilise 100 million young people with voices and idealism to work with 100 million young people who are victims of violence (not just slavery but trafficking, prostitution and those who are being denied their basic rights such as education and nutrition). Young people must be at the core of such a movement, and as Satyarthi told me, “They have a desire and hunger to prove themselves and do something good for society, and I want to engage those 100 million plus young people to become spokespeople, champions and change-makers for the 100 million that have been missed out. If young people take the driving seat of these campaigns, nobody will be left out.”

A Beautiful View of the Future

I asked Satyarthi what childhood should be. He paused for a moment, reflecting and then said, “…every child should free to be a child. Every child should be free to cry and laugh. Every child should be free to learn and grow. Every child should be free to play and enjoy his or her childhood. Freedom is the key to childhood, and we must protect that.”

“Childhood means simplicity, forgiveness, a quest for learning, working-together and transparency. It is a precious gift from God, and each of us must keep that close to our hearts for our whole lives.”

Asking how we (as a society) can reflect on our relationship with our children was- perhaps- the most telling.

“We have done so many good things for our children,” Satyarthi told me, “but the worst thing we’ve done is to give them a divisive identity that says they are Hindu, Muslim or Christian. We have taught them they are American, Indian or African. Children have never created borders, religions, faiths or caste systems. Children have not been responsible for wars and divisions in society- we did that… and now we’re imposing on our children, from their birth, a divisive image of who they are. We need to learn from children, and learn simplicity, forgiveness and the beauty of life.”