Negotiation is stressful. It can bring out the worst in people. Wouldn’t it be better if there were a principled way to negotiate? Wouldn’t it be even better if there were a way to treat people fairly and get treated fairly in a negotiation?

Barry Nalebuff is the Milton Steinbach Professor at the Yale School of Management. Nalebuff applies game theory to business strategy and is the co-founder of one of America’s fastest-growing companies, Honest Tea. In his new book, SPLIT THE PIE: A Radical New Way to Negotiate he outlines his tried and tested practical negotiation methods that reveal the true power of the players and what they bring to the table. From years of real-world negotiation, and deep research on game theory, Nalebuff identifies what’s really at stake in a negotiation: the “pie.” In his model, the negotiation pie is the additional value created through an agreement to work together. Seeing the relevant pie will change how you think about fairness and power in negotiation. You’ll learn how to get half the value you create, no matter your size.

In this interview I speak to Professor Barry Nalebuff about how we can apply his negotiation model to understand and reframe everything from every-day to high-stakes negotiations. We delve into the psychology of the negotiation and how deploying empathy can help reach great solutions.

Q: Can you talk us through the concept of the negotiation pie?

[Barry Nalebuff]: The idea of the negotiation pie comes from game theory.

I was teaching negotiation and wanted a theoretical framework to present to the students. I wanted a theory that continued to work when people on both sides understand what the theory is.

A lot of negotiation is teaching people tricks or verbal games, as opposed to providing a framework for thinking about negotiation and I also feel that people want to come up with a solution that’s fair. But what they think of as fair is often proportional division, and that just arises because they don’t really understand what they’re negotiating over and that leads them to conflicting views of fairness, which often then leads to no agreement or hard feelings.

People don’t know what it is that they’re negotiating over… If you don’t, then it’s hard to know if you’ve gotten a bad deal, a fair deal, or a great deal! That’s going to lead us to the negotiation pie, and with the negotiation pie comes the extra value that negotiators create by coming together.

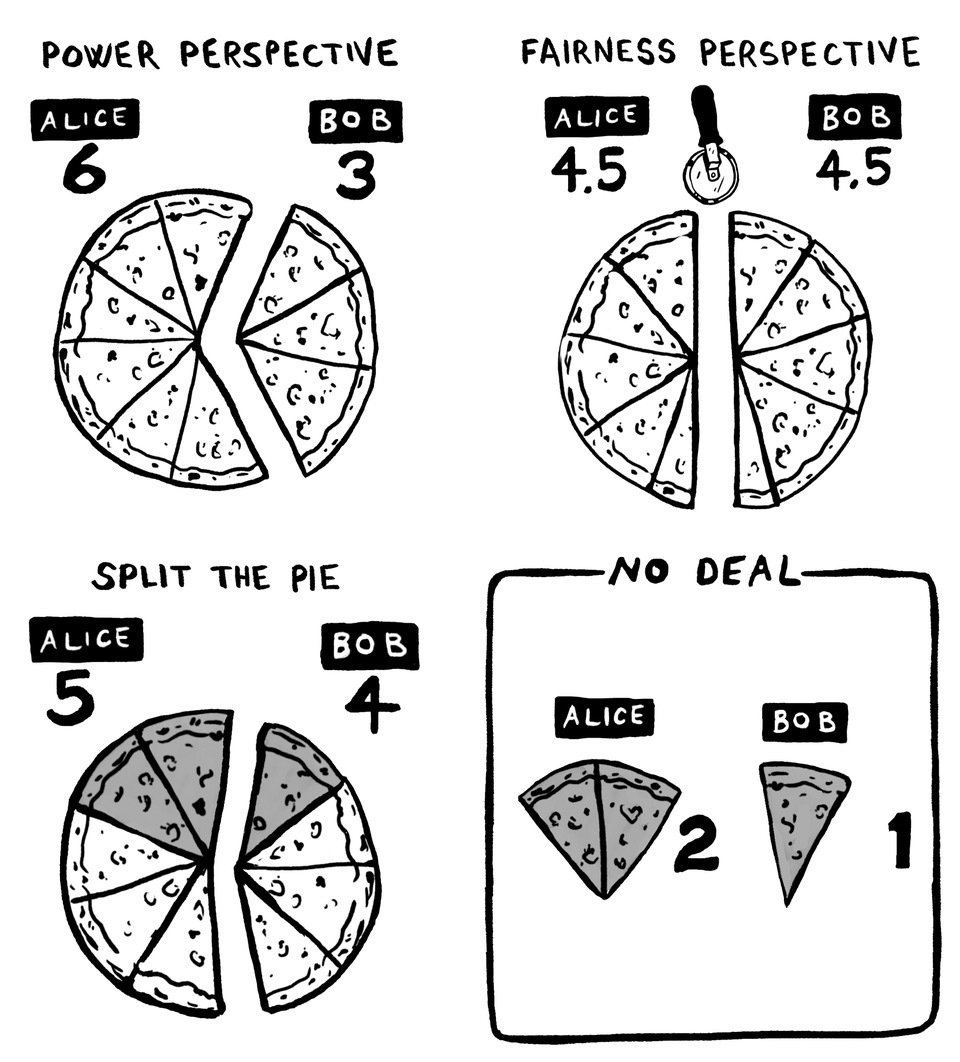

Let me give you an example… Let’s say we have a 12-slice pizza that Alice and Bob can divide up if they can agree on how to divide it up. If they don’t reach an agreement, Alice will get four slices and Bob will get two. Now, a lot of people might think that Alice is twice as strong as Bob. So therefore, Alice, you get twice as much – an eight to four division. Other people think that fairness means you take the 12 slices and divide it ‘6:6’. My view is neither of those things are correct – that if they don’t reach an agreement, they can get four plus two slices or six slices. If they do reach an agreement, they can get 12. So, the point of the negotiation is to go from 6:12 slices to get those extra six Alice and Bob are equally needed, and therefore you should divide it up three and three, which means Alice gets 4 + 3 or 7 and Bob gets 2 + 3, which is 5 slices.

Q: How can we best understand the early dynamics of a negotiation?

[Barry Nalebuff]: I think the people who are larger or those who have more resources like to think they’re the ones who have greater power… and they have benefited from that illusion.

Let me share with you a story of my own life, which I think helps illustrate that.

I was involved in a negotiation over a domain name with a troll. This troll had bought the domain name for a company that I was starting, and I needed to get it back. The domain name was worth a large amount of money to me, let’s say $10,000. When I wrote to this troll, I’ll call him Edward because that was his name, he said he’d sell it to me for $2500! So already that was a good thing because it was less than what I was willing to pay. But… I did a little research and discovered that I can engage the domain registry in a dispute resolution process that I was sure to win because I had registered the trademark and going through that process would cost $1300. So, I said to him, ‘look, I’d rather pay $1300 and have you get nothing than pay you $2500 in both cases, I’ll get the domain name’. So, the first question is, who has more power here? In some ways you could say, I was a weak position because I totally needed it. It was worth $10,000 to me and say, well, he was in a weak position because if we don’t reach an agreement, he gets zero. But I think both of those things are misguided. At the end of the day, we’re not negotiating of my ten-thousand-dollar value, we’re negotiating over the ability to save the $1300 that I would have to spend to rescue the domain from the troll. And to do that, I need his cooperation and he needs my money. And so, I think we’re equally necessary here. So, Edward comes down to $1100 when I point out to him that I’d rather spend 1300. At that point, I explained to him the theory of the pie and say ‘Look, there’s $1300 to split. I’ll give you 650. You can make 650, but I’m not going to pay any more than that’. He says, 900 [dollars] is his last offer. And I stopped writing to him. A week later, it comes back and says ‘OK, I’ll take your 650’.

Now the question is who had more power here? …making arbitrary claims, picking random numbers out of the hat, trying to first psyche me out with a high number and at the end of the day, I had a principle which was just pure dollar we both needed. He had no principle and so that’s what ultimately led us to split the pie.

Q: How do we negotiate when people don’t care about fairness?

[Barry Nalebuff]: Edward [the domain troll] didn’t’ care about fairness. He didn’t’ care about the pie. All he cared about is money. But he also recognised fairness, and therefore, in his essence, I was able to make an ultimatum.

I was saying, ‘you need to treat me fairly if you want to reach this deal or we’re going to do nothing.’ And he didn’t have any other principle to fall back on. Sometimes it doesn’t matter if the other side doesn’t care about fairness; provided you do, you explain what’s going on. I’m now playing his game and I pick something that’s arbitrary. And now it’s arbitrary vs. arbitrary versus principle versus arbitrary.

Q: How do you start a negotiation well?

[Barry Nalebuff]: There are three ways that people start negotiations. I think the worst way is to start off with is price – just to throw a number out there – that’s my least favourite way of starting.

What I like the most and essentially is never done is to start off a negotiation by talking about how you’ll negotiate, what’s the process going to be? And to say things like ‘my goal in this negotiation is to reach an agreement with you in which we create a giant pie and split it evenly and can we agree that that’s our goal?’ And if so, now we’ve resolved the issue of division and we can work together to create a great pie. If you don’t agree with that, now I know what kind of person I’m dealing with, and so I must have my guard up the entire time.

Q: How do we modify our negotiation process for the virtual world?

[Barry Nalebuff]: Perhaps the virtual world makes it even more important to talk about process, rather than less, because it’s so easy to have misunderstandings that occur on email… even for people who like each other… never mind people who are in a potentially antagonistic relationship! So, I would certainly recommend Zoom over email and email over writing letters back and forth. It’s a quicker chance to fix misunderstandings. But it says ‘what are the ground rules? In particular, if we create some giant pie, how do I know that I’m going to get part of it?’ And if we can resolve the hard part first, then it allows us to build a lot of trust.

Q: How do we mutually agree the principles of what the pie is that we’re negotiating over?

[Barry Nalebuff]: Oftentimes, that’s a data question… So let me again use an example of my own life. I had the good fortune of working with one of my former students, Seth Goldman, to create a company called Honest Tea. And when it came time for Coca-Cola to buy the company there was a question of how much they would end up paying for it. At the time, our sales were around $23 million, and Coca-Cola’s great at bringing a company from 100 million to a billion. But they’re also pretty good at taking a company from $50 million down to zero. They were afraid that if they bought us now, we would get lost in the system. We agreed that they would buy us in three years. But then there was the question of how much they’d pay. Essentially, they were going to help us during those next three years with distribution, with production, with purchasing and they said, well look, you know, we’re going to help you in all these things, but we don’t want to pay for the value that we create. My response was, you should pay half for that because you can’t do without us, and we can’t do without you. You should pay full price for sales up to X and half price for sales that we achieve beyond X that we couldn’t have achieved without you.

So, we agreed upfront that we create this big pie and we’d split it and then we spent a week or more arguing about what X would be and what full price was. In some ways, we didn’t even have to agree today what the pie is, because if we could measure what the pie would be in the future, we agreed that we’d split it whatever it ended up being.

Q: How do you know the cards to show in a negotiation?

[Barry Nalebuff]: I am way out at the extreme in terms of revealing things. In terms of my negotiation with Edward (the troll) I revealed my position, which was paying $1300. I don’t think that put me in a weak position, because in essence, that’s what got him down from 2500 [dollars] right to 1100 [dollars] and then ultimately allowed us to split the pie at 650 [dollars]. I think people all the time, hide or lie about information that would be useful to share.

If you think about somebody who’s selling their business because they want to climb the seven summits and they think, Oh… that’s sort of embarrassing, it’s selfish ….and so they say, I’m doing it because I’m retiring.

Well, first off, the person who’s buying the company knows there’s some reason you’re selling and there are good and bad reasons you’re selling. A bad reason could be the business is in an industrially polluted site and there’s going to be a toxic clean-up, and it’s going to cost a huge amount of money to fix that… So the fact that I want to take this trip is actually a great reason from the buyer’s perspective, not a bad reason.

We hide things that are ultimately good reasons.

Q: What are the common reasons that negotiations fail?

[Barry Nalebuff]: Most of us have never been trained in negotiations so we copy things we see on TV or what we imagine from her or from bellicose presidents. Those are not tactics that I would recommend!

The first thing I’d say is a big mistake is not caring about what the other side wants. If this person wants to go climb the seven summits, my job is to figure out how to make that happen, because if they get to do that, then I get to do what I want, which is to buy their business. Oftentimes people are thinking I have to say no to the other side. My goal is to say yes to them. It’s to figure out what it is they want and give it to them. What else do they want besides money so that I can help them achieve their dreams and thereby make them happy in terms of selling to me?

Another common mistake is just not planning… you must anticipate what the other side will object to, based on what you’re proposing. Essentially, it’s the old line – no battle plan survives first contact with the enemy. You should be flexible, and you should have a series of contingencies… I think you want to make the other side’s arguments rather than negate them.

And one reason people are often arguing is they think they’re not getting their way because you don’t appreciate their arguments.

Q: Can we apply the negotiation pie concept over qualitative rather than quantitative negotiations?

[Barry Nalebuff]: In the end you do have to make trade-offs whether you put dollars on them or points on them or utility numbers on them, sometimes you have to say, look is it worth a week in Majorca versus doing the dishes?

Whatever it is that you’re trying to choose between, you must think about whether the outcome is making you happier or not making you happier. There is the combined happiness of the two sides. What I like to do is think about, in some sense, putting each side on a zero to one scale where 0 is, I’m getting nothing of what I want, and 1 is getting 100 percent of everything I want and what’s the solution which gives us both the equal and highest percentage.

What solution is the one which maximises the common percentage of both of our ideals?

Q: How can we best understand our anchor, and avoid getting sunk by it?

[Barry Nalebuff]: Anchoring is an area where behavioural decision making has gone overboard, and a lot of folks say you should start off with a radical point – anchor the other side – so later they will think you will be reasonable!

It all comes from early work by Kahneman and Tversky, where they showed that if you ask people how many African countries there are in the United Nation and anchor the question with a figure (is it above or below X) – that first number influences their final estimate. When you or I use these anchors, nobody gets ma… in general…. But when Trump negotiates with the President of Mexico, Enrique Pena Nieto and says My starting point is ‘You’re going to pay for the whole wall’. His response is ‘screw you. I’m not even going to come to Washington to have the conversation. We’re done’.

In a negotiation, my view is that you should try and pick a number that you can justify. So, if somebody says, ‘How did you come you with number?’ you have an answer.

Q: Should we ever walk away from a negotiation?

[Barry Nalebuff]: Not all negotiations are solvable… In fact, one of the things you should try to discover early on is if there’s a ‘there’, there! because otherwise you’re going to waste a lot of time to get people frustrated.

There’s a software tool that I once developed and ultimately failed with, which was based on the idea of information escrow, and in that each side puts their number in an envelope, if you’d like. You say the most you’re willing to pay, the other side puts down the least they’re willing to accept. If those two numbers cross, a solicitor or a computer programme will tell you they cross but won’t tell you either number. If they don’t cross, they’ll say there’s no deal there and you can walk away quickly.

One of the big mistakes many of my students make is they accept deals that are worse than no deal. That’s the cardinal sin of negotiation – to let the process get you carried away so that you in fact take a deal that’s worse than ‘no deal.’

Q: How can we be better negotiators?

[Barry Nalebuff]: You want to convince the other side that you care about them. What’s the best way? …it’s to care about them! It’s not a manufactured empathy… it’s to be curious and empathetic, and we somehow think, instead, you have to trick them into revealing their hidden number or have to fool them by softening them up with this high opening bid…you have to act like a jerk, or they think that’s what you need to do.

So, the first lesson we must do is get off these stereotypes and play to our strengths, not to the other side’s weaknesses. You also must give a framework, one which can work no matter which side you’re on.