All of us face challenges, rough patches and struggles in life. During these times we are often our own worst enemy, experiencing unwelcome emotions, thinking and behaviours.

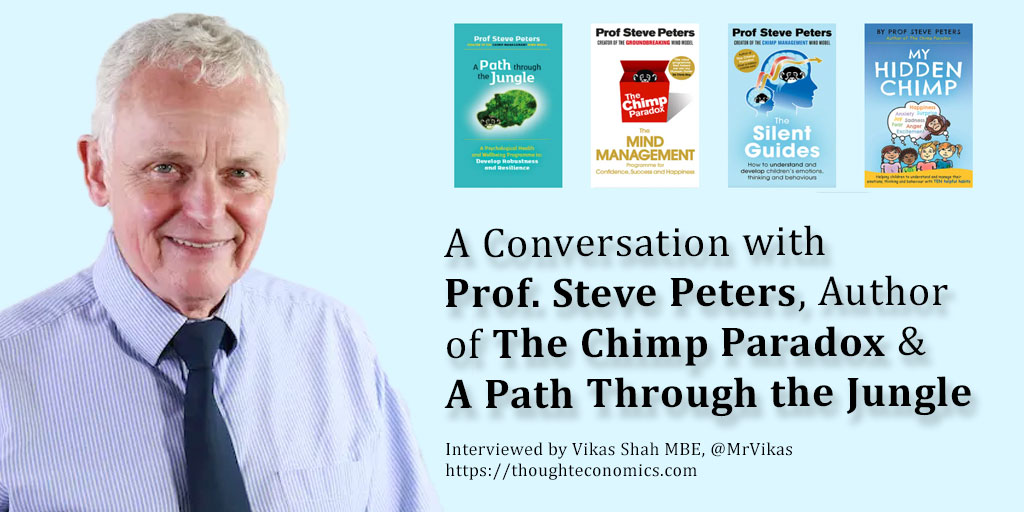

Professor Steve Peters is author of the bestselling book, The Chimp Paradox, which has sold over 1.4 million copies since release in 2012. In his latest book, A Path Through the Jungle, he has created a practical self-development program to help readers and listeners attain psychological health and wellbeing and to find empowerment, robustness and resilience.

Professor Steve Peters is a Consultant Psychiatrist who specialises in the functioning of the human mind. His work, past and present, in the field of psychiatry and education, includes: the National Health Service (NHS) for over 20 years; Clinical Director of Mental Health Services; Clinical Director at Bassetlaw Hospital; Forensic Psychiatrist at Rampton; Senior Clinical Lecturer of Medicine at Sheffield University for over 20 years; Undergraduate Dean at Sheffield University for over 10 years; and visiting Professor at Derby University. He has been a consultant to over 20 Olympic and national sporting teams including Liverpool FC, British Cycling, GB Taekwondo, England Rugby and England Football. Outside elite sport, Prof Peters works with CEOs, senior executives, teachers, students, hospital staff and patients. Steven Gerrard, Sir Chris Hoy, Ronnie O’Sullivan, Victoria Pendleton, Katarina Johnson-Thompson, Lee Westwood, Jonathan Trott and Raheem Sterling are individuals who have all spoken publicly about how Prof Peters’ has helped them during their career.

In this interview, I speak to Professor Steve Peters on The Chimp Paradox, A Path Through the Jungle, how we can focus and empower ourselves, be better leaders, and find a path to robustness and resilience.

Q: How did you start to understand the mind?

[Steven Peters]: I was working in the NHS as a consultant psychiatrist for many years, and what struck me was the distinct difference between those individuals who came in with mental illnesses which meant we had to intervene to help – and those who came in with minds which were largely in good working order. Think of lit like a car – you could have a car which is in perfect working order, but if you don’t know how to drive it, you’ll keep getting things wrong! If you know what’s inside your head and you understand its structures, rules, and functions, it avoids glitches.

Around 30 years ago, I started to explain this to the people I was working with in my clinical and consulting practice. I took them through the process of understanding the basics of their mind and a machine before adding more depth to it. This is a very complex machine we’re talking about – so in the late 1990s, I introduce the idea of simplifying the mind into 3 teams that our consciousness is aware of. Firstly, our conscious selves as a person, secondly our primitive survival system (our inner chimp) and thirdly a computer.

You can almost think of it like three sock puppets! You, this little chimp, and a computer, trying to run your life.

Q: How should we best understand emotions?

[Steven Peters]: The primitive system we’ve inherited is trying its best to work for us, but often goes against what we want. It starts just above our eyes in the orbitofrontal cortex, which works on a very principle – that something is either good or bad. This part of our brain learns behaviourally and is responsible for a ‘go/no-go’ decision. If you try something that works? … go. If you try something that doesn’t work? …no go, try something different. The brain must encourage us to do more of what works, and in order to do that, it gives us emotion. If we chat to someone we like, we want to go and meet them again because of a pleasant feeling or emotion. If we meet someone we don’t like, we get an unpleasant feeling, so we feel inhibited and try someone else. This is how our brain works and we see that across the whole of our behavioural approach to life.

Emotions are like the reward (or punishment) the brain gives us for getting what we need, want, or could be harmed by.

Q: What are robustness and resilience?

[Steven Peters]: When we have a word to describe something, it enables us to manage that ‘thing’ much more actively. Words are great tools, and we know that people who articulate and express themselves with the right words do well, and children – when they can’t – get frustrated and act out.

I define robustness as saying that we’re fit for purpose, ‘I’m sat in my house in the morning, I’m in a great place, I’m robust and ready to face the world and deal with any emotions my brain throws up’ It’s having a plan and being ready. Once I open the door and life happens to me, I’ve got to say robust, that’s resilience.

Robustness is being in a good place and having a plan, resilience is being able to implement that plan and stay in a good place.

Q: Do we have ‘stabilisers’ in our mind?

[Steven Peters]: When it dawned on me that there were these three systems (the chimp, the computer, and the human), it also made me realise that only two of these are fundamental decision makers – the human and the chimp – only one of which we’re in control of.

For the human, stabilisers are working with values, the reality of life, the truth, and perspective. We know the parts of the brain that do that – and we know that if we put together these stabilisers, our ‘human’ will get stability.

However, the chimp does not work with any of that, and has the power to knock us out. We can sit there and go through our perspective, reality and values but when we try to implement we can fall apart and get emotional. The rules of the brain are such that the chimp can freeze our brain, freezing the human out and can make decisions on our behalf. This links back to the primitive role of emotion. The chimp looks externally – values, acceptance and reality are internal things – they’re for our head to work out and impose outside. The chimp cannot do that. The orbitofrontal cortex is a system which necessarily looks outwards for stability. That’s why friends, family, people on our side, our tribe mean so much to us. That’s what the chimp works with.

The third system is the computer. If we, the human, program the computer and really bring to life our values and perspective, then when the chimp is about to look externally and panic, the brain sends the message in a big circle through the computer to inform the chimp. That can have a massive calming effect and give resilience to the chimp.

When the computer fails, which it can, the chimp looks externally and can panic.

My advice is to grab hold of people that are close to you and lean on them heavily. That’s how we’re designed to work!

Q: How can we deal with major life events?

[Steven Peters]: Let’s deal with two examples of life events. A change in circumstances, and a bereavement.

A change of circumstance might be uncomfortable, but you’ve got to put up with it. So, your system has rules…The chimp and the human pick-up this situation occurring – the chimp knocks the human out, and makes decisions on what it will do – it’s emotionally reactive – but spins through the computer system to check if there’s anything it needs to know. If there’s nothing coming back, we get an emotional, impulsive, response which can be catastrophic – causing us to ‘fall apart.’ We start grieving about our situation – the chimp eventually settles down over time…. If we program the computer with the correct beliefs, the chimp won’t go through that – and – even better – the computer can take over and give the chimp a measured response!

If you suffer a bereavement, say the loss of a loved one, initially the same happens. The chimp reacts, the human gets knocked out, and the chimp looks to the computer for valid beliefs – however – if the significance of the event is very important, we can’t just stop and accept the situation using the computer. After a close bereavement, it can take years to come to terms with what’s happened, and usually around 3 months to get over the various stages of grief. It takes the chimp time, and we can help the chimp’s brain come to terms with that.

You can work with your mind to accept change and loss, but you must also accept that in severe cases, you can be left with emotional scarring which means that you must learn to live with what’s happened – and manage the scars which hurt us- and prevent them from doing so.

Q: What are habits, and how can we change them?

[Steven Peters]: Some habits are based on our reward system, and others are based on our fundamental drives for security, sex, and food. You have to be careful to divide the drive from the behavioural habit. There are some habits like going to bed at a certain time, or having a milky drink at night, where we just get into a habit and feel incomplete if we don’t perform those tasks. Those are behavioural habits which can be changed fairly-readily.

As we develop a habit – it is effectively the brain developing a pathway – and that pathway repeats as long as it works. So if we have a pathway that we believe is working, we’re not going to change the habit! If we think there’s a better habit, but the reward is not powerful enough, we’re not going to change the habit unless we increase the reward or increase the suffering the original habit causes.

Changing a habit requires effort as we must disintegrate the old pathway or form a new one. It’s rare but not impossible that a habit can change spontaneously in the face of new information, but in general, habits are broken by effort. We need to change our brain’s perception of what normal is – and that causes us to normalise the new habit. We have to work with our computer and chimp systems to overturn the present and normalise the new.

Q: Why are we not taught more about emotional & mental management?

[Steven Peters]: If you imagine you’re 100 years old, you’re on your deathbed with minutes to live and someone asks, ‘what should I do with my life?’ – maybe you’ll tell them, ‘be happy, don’t worry, live your life…’ – that’s nice, but not helpful. It’s common sense, right? What would be helpful is to give specific guidance – and that’s what I’m trying to do.

The reason we can’t be happy, and not worry about other people’s opinions, is that we’re sharing our minds with a machine that does worry about other people’s opinions and which does get anxious. If we can dissociate from that, and learn to manage it, it can improve our lives significantly.

Research shows that if you start teaching resilience strategies to a 4-year-old, by the time they’re 14, they’ll be measurably more resilient as teenagers. It’s absolutely crucial to get young children to understand resilience. Even adults can learn though… we can learn about what overwhelms us… what hijacks us… and learn how to stop it.

[Vikas: this links to the cultural notion of ‘happiness’ doesn’t it, and that fallacy of culture pushing this ‘always be happy’ narrative?]

[Steven Peters]: We all hope to have happiness in our lives, but we can’t always be happy. We can increase the probability of happiness in our lives, but life will still throw us around. Nobody is always happy. We can become resilient however, and learn to have peace of mind, even when we experience traumatic events. We can learn to have stable peace of mind… happiness? Maybe not.

I’m just one man, with one model and one experience. It may not be for everyone, and there are lots of models out there. It’s important to find what works for you individually to help you become resilient, and at peace.

It’s unhelpful to say to someone, ‘do these 10 things to be happy’ – there are things you can do to get peace of mind, increase your probability of happiness, and your probability of having successful relationships. That’s what we should focus on.

Research done on lottery winners clearly shows that 2 years on, they’re no happier. That’s not to say that life isn’t tough without money – but if we start to think that money will bring us happiness, the research tells us otherwise. We have to really deep-down look at what the real things are that we need for happiness, and the evidence from research on this.

I don’t think there’s any rights or wrongs in any of it, it’s just exploring where you really feel your happiness or peace of mind is going to come – how do you get that, what’s really going to hit the nail on the head for you?

Q: Can better understanding our mind help us build better relationships?

[Steven Peters]: Learning how we think and behave unlocks how others think and behave. I’ve been humbled by people who read my book and said it saved their marriage. I always tell them the book didn’t do it… they did!

I’m just bringing the science to the table and saying very simple evidence-based things. For example, when you’re having a conversation with a loved one or colleague, the chimp brain always wants to speak first and get in. The human brain, however, likes to listen. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex likes to listen, gather facts, and understand what it will say. We know that if we learn to stop and say, ‘let me hear what the other person says first…’ it will likely be a much more positive interaction – if we speak first, it’s less likely to be productive.

Now obviously you’ve got to temper that to say what’s appropriate in the moment, but as a golden rule, learning a new behaviour of going to human circuits and listening, can really alter relationships, both professional and personal.

Q: What do you hope your legacy will be?

[Steven Peters]: I don’t really think about legacy- I don’t really want to be remembered.

With the money I’ve made from the books, I’ve bought a centre where I live, and my legacy is that I want to leave behind a psychological health centre where people who haven’t got the money can come to get help. I want that to be operational so I can live out what I’ve always tried to do; and that’s to help people get to a great place psychologically within themselves. That’s my dream, and perhaps a legacy, but I don’t necessarily want to be remembered.

I’ve refined The Chimp Paradox in A Path Through the Jungle, and I hope that someone will pick that up one day refine it and make it better still. They’re welcome to.

I don’t mind being forgotten. I’m quite comfortable being forgotten.