By any measure, the United Kingdom is a rich country. We are a nation with over £10 trillion in assets (£6 trillion of which is privately held), and depending on your measure – we are the 5th or 9th largest economy in the world. From the outside, we are a success story; with booming sectors ranging from technology to finance, a seat at the table of global diplomacy, and cultural power internationally.

It is perhaps because of this success that we should be surprised, ashamed and appalled by the fact that 21% of our population, some 14.2 million people, are living in poverty. One in ten of our population (some 7.7 million people) has been entrenched in persistent poverty for at least two of the past three years. Our success hides the fact that the richest 10% of households hold close to 50% of the entire nation’s wealth, whilst the poorest 50% own just 8%.

In the 1980’s, a sudden deregulation of financial markets (the Big Bang) in London coincided with the incredible growth of financial, professional and service sector businesses – against a declining industrial sector; this created extraordinary wealth and prosperity for a slice of our population, and a two-tier economy that has left many behind.

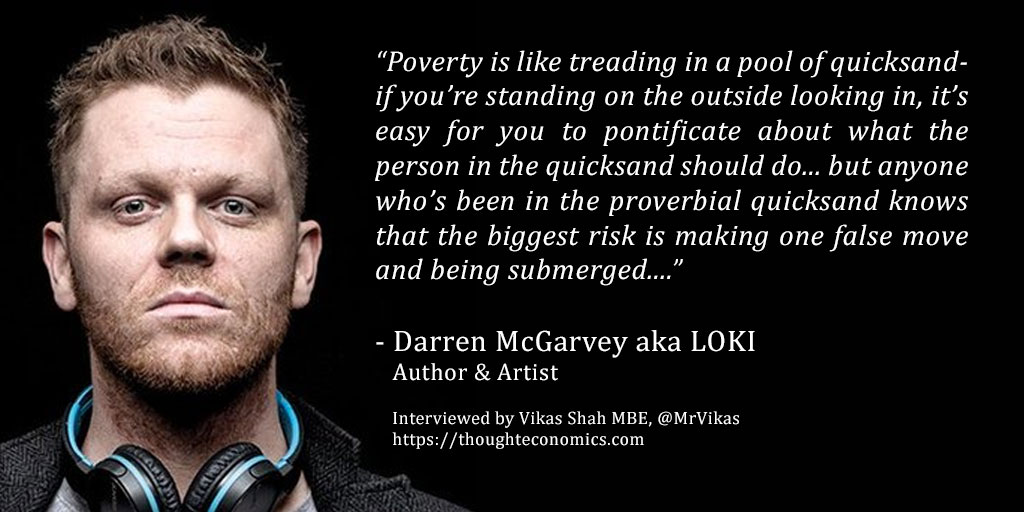

Darren McGarvey, aka LOKI, grew up in Pollok. He is a writer, performer, community activist and columnist, and former rapper-in-residence at Police Scotland’s Violence Reduction Unit. He was part of the Poverty Truth Commission that was hosted in Glasgow in 2009 and has presented eight programmes for BBC Scotland exploring the root causes of anti-social behaviour and social deprivation. In 2018, he published the seminal book Poverty Safari which gives voice to the feelings and concerns of deprived communities I caught up with Darren to learn about the realities of poverty in the UK.

Q: What characterises the experience of poverty in the UK?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: There is a popular belief that poverty is characterised by social factors – low wages, addiction, and violence. These things all exist, but what really characterises the experience of poverty is emotional stress.

Children growing up in a household living in poverty experience emotional stress for their parents who are trying to manage a household whilst living with low wages, violence in the community, addiction and more. Stress is a natural human response to emotional strain, and whilst it can be useful in short doses as a catalyst, a motivator, a wake-up call, in the long term it can impact development, damage relationships and lead to self-defeating compulsive, addictive behaviours which have their own problems and dangers.

It is this experience of poverty, emotional stress, which is overlooked most often- perhaps because the people analysing poverty don’t have a visceral insight into it.

If you understand poverty in terms of emotional stress, it explains a lot of the behaviours associated with people- particularly those experiencing worklessness, and who might be engaging in criminality and making poor lifestyle choices when it comes to health, drug-use and alcoholism.

If we look at people’s lives through the lens of stress, things make sense.

Q: Do we need to change our language when speaking about poverty?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: The issue of poverty is so large, that I try not to get too bogged down in the minutiae of the language we use to describe it. It’s obviously unhelpful to characterise people who are living in social inequality as some singular monolith, with singular behaviours, intentions and minds – though we do this as humans, we characterise the rich, the poor, the other as singular groups. It’s how we make sense of groups we have no insight into.

It’s more important to explain and illustrate, as vividly as possible, some of the experiential realities people face, and ensure our language is broad enough to encompass this. When you look at those in poverty, you see subcategories of people even in the same group; Take for example those who are homeless – this could be from residential instability, family disfunction, precarity in work, and work poverty – but you also find many people who are socially excluded because of addictions, criminality and multiple other issues. You will find people who are dealing with homelessness, dysfunction, addiction- but we categorise them as ‘homeless’ and refer them to ‘homeless services.’

For example, if you look at the Department of Work and Pensions, and their current culture of welfare conditionality, it creates a distorted picture as to how many people are really claiming benefits, unemployed and in precarious low paid work. The DWP is often the front-line service these individuals see, and they [the DWP] simply aren’t equipped to deal with mental health problems, drugs, and alcohol abuse.

Imagine instead how it could be if health and mental health were integrated into social care.

If someone was going to be sanctioned for not making a meeting- instead of cutting their money and exacerbating the conditions that have led to their inability to meet their responsibilities- why not sanction them to go and see a doctor, a mental health worker, a psychologist, a counsellor.

Today’s welfare services aren’t linked with health, and it means people just slip through the net.

Currently, public services are extraordinarily hostile to those in poverty; a doctrine we’ve seen clearly in how the Home Office has handled the Windrush generation. This ideology believes people will respond positively to being treated with hostility; but that only works for emotionally regulated people who didn’t grow-up in adversity, and so can respond positively to that kind of incentive.

Our public services are emotionally illiterate.

Q: What are your views on how law enforcement is engaging with communities impacted by poverty?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: There have been tens of thousands of cuts to policing, and that means- immediately- that the police will adopt their most basic configuration, policing by force not consent… and without goodwill from the community.

In Scotland, we’re leading the way in recognising violence as a public health issue as well as a criminal justice issue. Certain police forces are given the opportunity to adopt new strategies like engaging with certain groups of young people, offering diverse activities, and working with people in prison to get them plugged into housing, welfare and services- so that when they come out, they’re set-up rather than facing an obstacle course. Wherever they’ve been tried in the United States, London and even Glasgow, these approaches have worked- but they require specific expertise and political courage. They require a politician to look a certain enfranchised electorally powerful demographic in the eye and say, ‘look, I know you feel strongly about law and order, and punishment, but the evidence shows you’re wrong- and I will show you the arguments behind why we need to look at this in a new way…’

Q: Are politicians leading on poverty?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: Todays’ politicians can’t lead public opinion, because they’re frightened of it – and we’re so consumed by constitutional crises, that there’s just no real chance that politicians can give these issues sufficient thought.

It’s a very precarious situation we’re in right now; and the biproduct of our current policies is that a tidal wave of radioactive social problems is coming. I worry that we’ll just repeat the mistakes of the past where drug addictions, drug related deaths, alcoholism and suicide spike out of control.

Q: Why do people feel so disconnected from policy and democracy?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: Whilst I don’t agree for example, with the conclusions that people draw on issues like immigration, and their anger and disaffection about it, I do think that people who haven’t benefitted from decades of neo-liberal prosperity are right in their assessment that democracy does work for certain people, but not for them.

I saw a poll recently that said that 40% of people would vote for a new centre-ground party- and I see the appeal of a third-way that tries to reconcile left and right, but without something truly radical, we’re not going to get anywhere. It saddens me to think that it feels like a radical idea to suggest that we should tax Amazon and Apple fairly- but these are radical ideas which would help us deal with challenges around residential instability, social housing, community funding, and worklessness. There are projects which have to be initiated by the sate, not incentivised by profit motives.

Q: What do you wish people understood about homelessness?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: The main issue around homelessness is simple- there aren’t enough homes for people. That’s the fundamental, systemic fact, that a lot of well-meaning acts of charity don’t address; and that includes homelessness charities.

Using the trope of one person to transcend adversity, even when that person is framed in a positive manner, creates a misconception – it misses the systemic context, the lack of social housing, and a system that is very difficult for people to navigate if they are experiencing adversities.

People who are homeless are less likely to be literate of, and confident about, managing multiple meetings, people and the rotating cast of support workers and psychologists they are told to meet. When you’re dealing with conditions of emotional stress, these are issues that can become insurmountable.

For example, in Glasgow we’re piloting an initiative where officials from the council will go and engage with homeless people in the street and begin the process of identifying what benefits they’re entitled to on the streets, and helping them go through the form. That’s one simple example of just recalibrating a way, recalibrating a service.

We don’t need to throw out or burn our services, but see them through the eyes of the people you’re trying to reach- thinking about how we can modify our approach to make it easier.

We have reason to be optimistic, but until the public get angry enough about homelessness with politicians rather than the homeless, nothing will change. Politicians respond to public opinions that they believe are electorally significant.

Q: Do people have enough opportunity to get out of poverty?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: Poverty is like treading in a pool of quicksand- if you’re standing on the outside looking in, it’s easy for you to pontificate about what the person in the quicksand should do, how they should behave, what risks they should be able to take- but anyone who’s been in the proverbial quicksand knows that the biggest risk is that they make one move in the wrong direction, and submerge deeper.

Imagine you’re dealing with multiple adversities- low income, low employment opportunity, low educational attainment – the last thing on your mind is becoming an entrepreneur or going to university or college. You’re literally boxed-in with day today concerns which may seem narrow-minded to some people- but which could send you back to square one in life. That is the painful, humiliating and sometimes dangerous reality for vulnerable people.

We hear a lot of people say that folks living on the street need to ‘take responsibility’ – a phrase which has been courted by socially ambivalent, emotionally detached conservatives who think what works for them will work for everyone. If you tell people to take responsibility, you have to understand what you’re asking them to take responsibility for. We have to work alongside people and understand what they’re needs are, what barriers they face, and how we can support them- not chastise them.

Q: What is the role of the arts in giving people a voice?

[Darren “Loki” McGarvey]: I’m not a fan of preachy art that tries to break down who good people are, who bad people are, and which talks about inequality in vague moralistic terms. If you look at some of the cultures emerging from poverty- the Grime and Drill scenes for example; they have already been demonised by the Police in London- and a media who claim the music itself creates the violence. While that might be true to a certain extent- we’re in the age of social media where things escalate fast and where for many, grime and drill music are an expression of the futility of the situation faced particularly by young men. Think about grime and drill like the golden era of hip hop; much of which emerged from the same social discontent- oppression, racial tension, toxic masculinity, gang culture, police brutality and adversity. Whether it’s Guru, Gang Starr, Wu-Tang or their peers- they would reference literature, music, religious texts, and they were educated. What you see with grime and drill is really sort of like how far back we’ve walked educational attainment since the 80s and 90s where really the only thing these boys have to talk about is the propensity for violence. The only thing they have to defend, their only thing of value is their reputation, and while that may seem small minded looking on from a distance – when your reputation is the only currency you’re able to trade in, then it becomes very valuable.

It’s the social conditions that we need to look at and what really these artists are doing is offering us a commentary, whether they intend to or not, of what life looks like through their eyes – and we need to pay more attention to that.