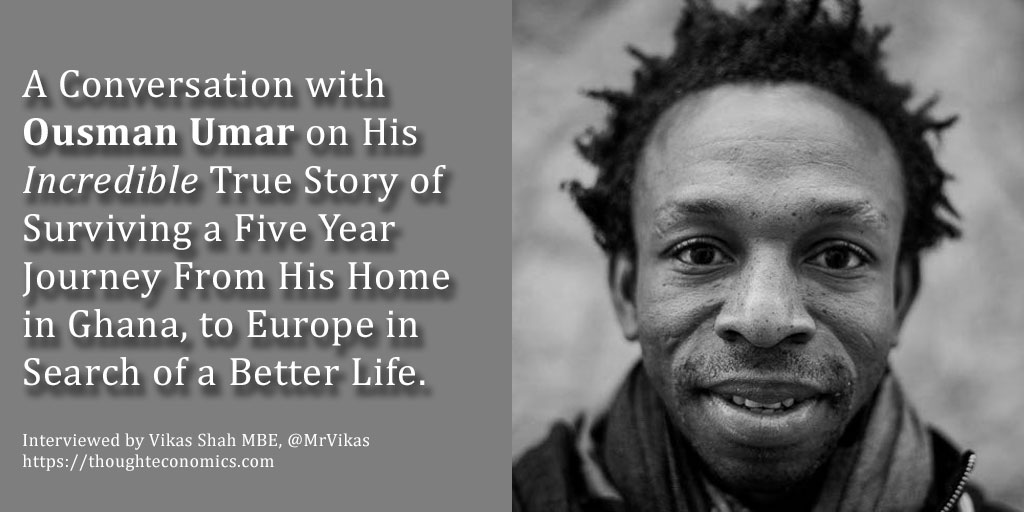

Ousman Umar is a shaman’s son, born in a small village in Ghana, and his mother died giving birth to him. The traditions of the Wala tribe dictate that this means the baby is cursed and must be abandoned and left to die. Fortunately, Ousman’s father was able to use his position as a shaman to save his son’s life. Ousman grew up working the fields, setting traps in the jungle, and living off the land. But he dreamed of a different life. So, when he was only twelve years old, he left his village and began what would become a five-year journey to Europe.

On a path rife with violence, exploitation, and racism, Ousman also encountered friendship, generosity, and hope. In his memoir, North to Paradise, Ousman tells his visceral true story about the stark realities of life along the most dangerous route traversed across Africa; it is also a portrait of extraordinary resilience in the face of unimaginable challenges, the beauty of kindness in strangers, and the power of giving back.

Ousman today is an entrepreneur and philanthropist. In 2012 he founded NASCO Feeding Minds, an NGO dedicated to the principle that the most effective way to prevent young people from leaving Ghana for Europe is to provide first-rate opportunities for education and advancement in Ghana.

In this interview, I speak to Ousman Umar about this treacherous boyhood journey from a rural village in Ghana, to the streets of Barcelona, and the path that led him home. We discuss why he, and so many, decide to migrate. We talk about the perils and realities of migration, and how we, as a society can deliver better aid, and stop the needless deaths caused by migration.

Q: Why did you leave and decide to go north?

[Ousman Umar]: Growing up, I saw all these raw materials being dug up from the ground, and I had this huge interest and curiosity to know where all these materials were going and how they transformed into the aeroplane I could see flying above me. How was it possible that this aeroplane could fly, and my toy car couldn’t even move a single metre by itself. Why did the stone that I threw in the air land on my head while that plan flies? Who were these white men I saw?

I had this curiosity, like Isaac Newton when he saw the apple fall and wondered why. People may have considered this a stupid question at the time, but it was his curiosity that led him to investigate, and he ended up discovering the force of gravity. Curiosity drives human progress; it helps us understand our world and that’s what drew me to leave my home.

Q: How did you prepare for your journey?

[Ousman Umar]: I left my hometown very, very young. I was around 9 years old. I was very capable and was able to manufacture little toy cars with the basic materials I found around me. Our neighbours in my village advised my father to send me to the city because of those skills. At the age of 9, I was sent to the nearest city to go to school. I walked 4 miles to the next village- the school was not free, and my parents could only afford for me to go one day here and there. My planning was therefore very limited. If someone had showed me a map and said, ‘Ousman, can you point to Europe?’ I wouldn’t have been able to.

Q: What drives you to speak about your journey?

[Ousman Umar]: I need to tell my story until there are no more stories like mine. More than 97% of my friends, with whom I shared this journey, died. They died around me, this isn’t hearsay, I saw it with my own eyes. In the Sahara Desert, out of 46 people who started the journey with me, some three terrible weeks later, only 6 survived. That doesn’t even include the dead bodies we found on the way. He was capable of urinating and drinking it was the most fortunate. Out of 46, 6 survived to reach Libya- governed at the time by one of the worst dictators on Earth, Muammar al-Qaddafi. Being black, and alive, was almost a crime there. I was 18 years old and stayed in Libya for 4 years. Reality overcomes fiction, I assure you. It took us 4 years to raise $1,800 each to go on the next step of our journey, crossing from Libya to Tunisia, to Algeria to Morocco. From Morocco we went to the Western Sahara and Mauritania. When we got to the sea crossing, we were split into two boats. There were 46 people on one boat, it sank, only 3 survived. On our second attempt at a boat crossing, we spent 48 hours at sea with no food and no water, only half the people made it.

I am not the strongest, I was the youngest and perhaps the most vulnerable. I had a sense of mission though, and every single one of us does. My mission to was to be voice for all those who died on my journey, and who kept on dying. My mission was to stop this happening.

Q: How did you keep your faith in humanity?

[Ousman Umar]: On my journey, I encountered the worst of humanity, and the best. I saw the truth of how awful humanity can be, and how generous. On our Sahara Desert crossing, there was a man, who was dying of thirst, who urinated in his hand and shared some with me when he needed it to survive. It’s easy to see the negatives in humanity, but it takes effort to see the positive. The world is about sharing and giving to others, I don’t have to focus on the individuals who want to destroy others.

In 2016, there was an image in the global media of the body of a 5-year-old Syrian boy who was dead on a beach in Turkey. Syrians are downing in the Mediterranean, and a lot of NGOs sent boats out to help. If you google images of rescues in the Mediterranean Sea, 80% of those people are not Syrian. They are African, sometimes Ghanian. Before 2016, Africans… black Africans… had been dying on beaches for years… how many images did we see of them on our news portals? Zero.

Q: How can we best help?

[Ousman Umar]: I finally ended-up in Spain in 2005. I think I was about 17- I don’t know my age- the only thing I know for sure is that I was born on a Tuesday. Imagine, I was 17, illiterate, sleeping on the streets of Spain without any Spanish or Catalan. I didn’t know how to read or write. It took me 6 years to overcome this, and to acquire a degree in University in Spain.

I am one man, but I feel the responsibility of being the Minister of Education for my people, for my country. I created one school, 10 years ago, and today, we have 43 schools benefitting from my initiative (NASCO, Feeding Minds). I don’t feed stomachs, I feed minds. Education is the only weapon capable of transforming a community.

To stop migration, we need to look at the source. It was very simple for me to understand that all my friends died due to a lack of access to information and education. My ambition is to be the voice of my friends who couldn’t make it, and who kept on dying. My mission is to avoid future victims. The way we do this is to create digital education systems. In Ghana, where I come from, that is how I am working to solve this problem – and today, more than 20,000 children have passed through our project without any government or institutional support. We are funded from the sales of my books, and from the money I earn from speaking at conferences. Through these donations we sustain 14 ICT schools in Ghana. This year, 6,000 students will pass through our 46 schools with no government support. Imagine… I was an illiterate 17-year-old boy, and I can do this. Imagine what we can do if we empower everyone.

Q: is international aid working?

[Ousman Umar]: We need to change the paradigm of international aid. The economist, Dambisa Moyo, showed that even though $2.5trillion has been invested in aid, Africa is now net-poorer than 50 years ago. Where has the money gone?

Imagine I came to your country with a bag of money and said that I will give you this money- but here’s what I want you to do. When I’m watching, you will do as I say, but when I turn my back, you will do what you want. You can’t force people to change- you have to find their passion and implement based on that. You can’t go to somewhere like Ghana and tell people what you think needs to be done. You need to understand the reality faced by the people you meet.

In my opinion, there are four basic principles of aid.

Respect; by which I mean full, humble, 360-degree respect for culture, ways of living, for each other’s humanity.

Humility; you need to listen. How can you help me, if you don’t know who I am? Listen and ask questions.

Ask; please, please ask before doing.

Action; if you say you’re going to do something, please follow-through. Trust can be broken very quickly. If people don’t want to be help, then please leave them alone.

Q: What are the biggest mistakes NGOs make?

[Ousman Umar]: NGOs often come to my part of the world with their own ideas. This is wrong. You must come with a fully blank mind. You need to be open to listening to people instead of thinking, ‘here’s my hammer, what can I fix?’ You need to detect the passion of the people – you need to listen – you need to get close to people, be their friend. You need to build trust, get people to open, share their passion and ask if they need help to make their passion come true. Change comes from teamwork, not from flying solo. Even Steve Jobs couldn’t build Apple on his own.

Q: What do you hope your legacy will be?

[Ousman Umar]: One of my aunts, who lives in a very small village, thinks I’m a lost cause. For her, success is the opposite of what I’m doing. Success for her means getting married to 1,2 or 3 women (polygamy is still accepted in some areas of Ghana) and for them to give birth to 5, 10, 15 children. For her, success means I cultivate my land. The word success is not defined well.

For me, success is the accumulation of failures without losing the illusion. Legacy for me is being the voice for all those people who don’t have a voice, and who keep on dying needlessly. Legacy for me is to make sure the world sees the people who they have not been interested to see before. If you have fair skin, and die at sea, everyone wants to know… if your skin colour is dark like mine? There’s no drama. Legacy for me means being a voice for all of those who didn’t make it and changing the aid paradigm to make sure that we avoid future victims falling into the trap of migration.