When it comes down to it, we’re just animals- like any other. Our sense of supremacy has however, given us the self-certified moral license to inflict incalculable cruelty on our fellow species.

In a typical year, we kill over 56 billion animals simply for food (10x the number of beings that exist in our population), use over 115 million (similar to the population of Japan) simply for experimentation and kill over 2 million (similar to the population of Qatar) simply for their fur. Alongside this, we keep over 500 million animals as pets, hold over 1 million vertebrates (our closest genetic ancestors) in our zoos and cause unimaginable suffering to tens of thousands in sport, entertainment, and mistreatment.

The epoch of our existence on this planet, and our demands on its land and climate have also accelerated the background rate of extinctions to over 100-1000 times the norm; thus referring to our time on this planet as being the sixth great extinction.

At this point in our story however, the narrative has changed. Science has shown our notion of supremacy was built on shaky foundations; and has illustrated clearly the toll we (as a species) are taking on the others we share our fragile planet with. In the past half century, figures have emerged leading the movement to educate us, and create lasting change – and one of the figureheads of this has been Virginia McKenna OBE, Founder of the Born Free Foundation.

I caught up with Virginia to learn more about humanity’s relationship with animals.

Q: Where did you find your passion for wildlife?

[Virginia McKenna] I started to get concerned about the natural world as a child and there are 2 images that I remember always from my childhood. The first was when I was around 6 years old.

My father took me to London Zoo, we went into the lion house (in those far off days they didn’t have an outside area, it was just an indoor house) There must have been about 4 or 5 cages in this building- and to this day, I remember the sound of the iron doors that clanged behind us as we went in. And there they were… these wretched creatures, walking up and down their very small caged area. I hated it! I absolutely hated it without knowing why really, at that age.

When I was about 11, I had a friend at school in South Africa whose family were going to the Kruger and invited me to go too – I was thrilled to bits and went with them! …in the Kruger, I saw a group of lions, obviously a pride, sitting peacefully and calmly under a tree. And these two contrasting images in a way became symbols for the rest of my life and the way I think about wildlife. One is how not to keep them, and one is how to leave them alone where they should be.

When my husband Bill Travers and I were asked to make the film ‘Born Free’ in Kenya, we had no clue about anything really! …but we said yes without thinking about it too much- and we learnt as we worked over the 10 or 11 months we were there.

Our great teacher was George Adamson who- through his own experience- not through books- but by getting to know individual lions- learned about their nature, how to read their body language (for safety reasons apart from anything else). George had a great devotion for these extraordinary creatures and made great friends with them as he did with some of the lions we worked with in the film. The lions we had in the film weren’t trained per se, as cubs they’d been pets as it were, in families: (two orphans were mascots for the Scots Guards Regiment in Nairobi), or they’d been orphaned and were in an animal orphanage in Nairobi. The first two they’d chosen were trained from a circus, but they proved to be too dangerous and so they didn’t work with us in the film.

Whilst the film formed a huge basis of our interest in the well-being of nature and animals, it was actually the death of an elephant that began our work in 1984. In 1968 we made a film in Kenya called ‘An Elephant called Slowly’. We were looking for a little elephant, and chose to film in Tsavo National Park, where the Sheldricks lived, as Daphne Sheldrick had already started her amazing work with orphaned animals. They didn’t have a very young one. They had teenage elephants but not a little one, and we needed that. So, David said that he’d heard there was a little elephant in the trapper’s yard in Nairobi, she’d been captured from the wild from her family by the government of those days, as a gift to London Zoo. She was waiting to be shipped to London, and we got permission to have her in our film. I was quite apprehensive. I thought she’d be so nervous and terrified, she wouldn’t be able to be calmed! But David Sheldrick was amazing, he calmed her and she was the most fantastic little creature. We became very, very fond of her. We asked if we could buy her at the end of the film to give her to the Sheldricks. They said we could but they’d have to capture another elephant, and we couldn’t tolerate that. Tragically she came to London Zoo where we learned about 12 or 13 years later, that there was a problem. They said they had discovered she had become very difficult. By then she was completely solitary (and as we all know elephants in the wild don’t really live alone unless they’re a solitary bull or something). The Zoo had decided they were going to put her down. We went to see her and it was one of the most heart-breaking experiences we ever had, as she recognised our voices and she came to us and touched our hands with her trunk.

I rushed around and managed to find someone in South Africa who said he would have her in his reserve, and I found someone to take her, be with her until she was integrated into the group, but the zoo wouldn’t allow this. They said they’d send her to Whipsnade which was better than where she was, because she’d have elephant companions there. Unfortunately the move was a failure because they’d kept her standing so long in her travelling crate that she collapsed. They got her up and she hobbled around in her den for a few days. They looked at her leg under anaesthetic, and then said ‘she’s lost the will to live’. So they put her down. It was her death that actually made us say ‘right, that’s it – we’ve talked a lot but we haven’t done anything. Now we’ve got to do something’. And that’s when Zoo Check began which is what we were called in those days.

Q: What is the scale of damage we have inflicted on the animal world?

[Virginia McKenna] The scale of our damage on the animal world is unimaginable.

We inflict pain and suffering on wild and domestic animals. We take away their wild lands and habitats, we use them to test our medicines and they’re affected by climate change, pollution and many other aspects of our world.

The physical trauma we cause animals is awful too; it’s not just hunting for example, but also trade in animals for food where they’re shunted around the world like bags of sugar.

On top of all this there are zoos, circuses, pest control and of course practices such as the Taiji dolphin drive, where thousands of dolphins are herded into a bay where they are surrounded and then captured for dolphinaria or killed. This kind of hunting is simply despicable.

We are the master race. We are the creatures who impose our will on virtually everything that lives and breathes. It’s deeply shocking when you start to think about the scale of it.

Pets are another area; I’m not against domestic pets, we’ve had dogs in our family forever! As long as domestic pets are loved, looked after and treated with respect – it’s fine. Having animals at home in a way, is good, because it allows us to understand the relationship between us and other species.

However, where you have puppy farms – for example- where a bitch is literally a breeding machine, that is absolutely out of order. How it is still legal I do not understand.

There is also the aspect of battery farming, for example with rabbits. One minute a rabbit is in a field being what it should be; the next thing it’s a pet in a cage, sometimes hopping about in the garden if it is lucky, and the next thing they want to open a battery rabbit farm so we can eat them like battery chickens.

Q: Do we need to extend our notion of rights to animals?

[Virginia McKenna] There have been well-known people who actually have advocated rights for great apes – chimps and orangs and gorillas. They’re our closest genetic relatives; but why should we exclude any creature that can suffer?

If you hold the paw of a little rabbit or a mouse or whatever so hard that it squeaks or screams, isn’t that cruel? isn’t that hurting it? What right have we got to hurt animals like that? We don’t have any right at all.

Q: Why don’t governments and corporates take animal rights more seriously?

[Virginia McKenna] Much of the mistreatment of animals is due to economics; it’s cheaper to raise animals for food when they’re kept in a confined “economical” way rather than letting them graze in fields… It’s cheaper to keep cows in a big shed where they never get out and fix them onto the machines to milk them.

That’s a dehumanising aspect of our relationship with animals.

If we can’t afford to keep food animals “kindly” – if we’re not thinking about them as breathing living creatures that suffer, then how can we even begin to consume them.

In my view, we should actually only have the free-range farms – meat would then be more expensive and more people would become vegetarian, vegan, and find alternative protein foods so that we don’t cause this terrible animal suffering.

One of the worst things for me is poor battery hens. I’m absolutely, totally opposed to a bird in a cage – “on a farm” or as a pet. Why does a bird have wings?

We always do the worst for animals instead of the best. And yet we’re depending on them, so many of us, for our survival. They deserve respect, but they’re not afforded it.

We’re all struggling to survive in a way; and we always should try and respect and understand animals, and be a little bit humble.

Wild animals have such a struggle to survive. Their land is taken away from them for crops or because people want to graze their cattle in it, so they are being squeezed out of the wild into such small areas that their prey animals will be severely reduced and the chance of long-term survival is small.

Q: What can we do to better the plight of animals?

[Virginia McKenna] It is very challenging!

We went on some marches last year to protest against elephants being killed for ivory, and sport hunting – the trophy hunting of lions and so on. One of the worst things about that aspect is in South Africa they breed lions in captivity, hundreds, they’ve got hundreds there, 600 or more lions in captivity! And when they’re killed, their bones and their skin are sold to the Far East. The bones are now often replacing tiger bones, because there are so few tigers left. There’s a product called ‘tiger bone wine’, which is extremely expensive and very sought after by rich people; and so lion bone is now going into this product.

Just think about that, they’re killing lions and marketing lion bones like bags of sugar in a supermarket, it’s just despicable.

The sale of ivory and rhino horn and lion trophy hunting are still carrying on. Nothing’s changed really, because I don’t think politicians on the whole have that as a priority on the whole. There’ll be an odd one, but not as a group.

Q: Can generational change and education help improve the plight of animals?

[Virginia McKenna] I was at one of our schools in Kenya recently, I was just chatting away to a group of children in their hall about all the things we had seen that day- the lions and how lucky they are to be sitting next to Meru National Park, and I said ‘would anyone like to ask me a question?’. Suddenly this little boy put up his hand and he said ‘please miss, why do men kill lions?’. Well, I could have hugged him if he wouldn’t have been mortified with embarrassment. But it was just the most fantastic thing that anyone could have said. And when I went again last year later on, I reminded their teacher of that little boy and what he’d said, and I asked if I could say hello to him and he came and said hello. He had understood the heart of it.

So one of the things we’re doing now, three times a year we’re going to take a little coach into the park with groups of children so they can actually spend the day there, have a picnic lunch and see the wildlife. I mean, you have to. Many Kenyan people do help already, but the children must know about it otherwise it will go.

I do quite a few talks to schools and I went not many weeks ago to one of my grandsons’ school. It was the pre-prep so they were very tiny. The teacher had said to me would I come and talk to them before they went to Chessington Zoo. I said I would love to come and talk to them, but I’d rather come after they’ve been to the zoo because I want to show them pictures of the same animals that they’ve seen in the zoo through my pictures of those animals in the wild, so they can see the difference. And I’m so glad I did that, because I was told about the animals they’d seen, then I found wonderful photographs of these same animals in nature. And of course, it was the liveliest session I can tell you, the hands were going up like sticks all the time!

It is absolutely right, it is the young eager questioning minds that you have to fill with the best things, not with—with the very limited experience that zoos offer. I mean quite frankly, I don’t think you learn anything from going to the zoo except how the animal looks. Because they can’t hunt if it’s a predator. It can’t have friends of its choice, it gets friends that are chosen for it, and it can’t do anything. It never, ever can escape from that existence. And to me that is a distortion of that wild animal’s life.

Q: What would be your advice to the next generation?

[Virginia McKenna] First of all if you go on holiday if you’re lucky enough to be in a family that can afford to go on holiday, and you’re going to go and see some wildlife, you could choose the tour operators that do not make an animal experience part of the trip.

When I say ‘animal experience’, I don’t mean going into a wildlife park in Kenya or Tanzania or something and seeing them in the wild… I mean circuses, or dolphin shows, elephant rides. A lot of travel companies have stopped doing that.

The contrast is so important, because otherwise the child just thinks ‘oh well that’s how this monkey lives’, or how this bird lives. They’ve got to be told the truth. They should never be fooled. We’re fooling them now, by taking them to zoos saying ‘oh the animals are very happy because they’re all fed nicely and put to bed at night’. That’s not how a wild animal should live. They’ve got no choice.

We like choice, why do we think animals don’t need choice? Of course they do! They choose their mate, they choose their friends, they choose where they live, what they eat. The same as us. And we deny that to them you see, don’t we?

Zoos are part of our culture going way back when, there have been zoos and menageries for hundreds and hundreds of years. And they were ghastlier before. We used to have bear baiting and fighting (we still have bulls fighting of course which is a relic from the past. But even in Spain, in some cities, they don’t have it anymore).

There is a change, but it’s a very slow speed change. It’s very quietly done, and there’s not much noise about it. People say ‘oh but safari parks are fine aren’t they?’. I say ‘well, they’re better than a cage in a zoo, but they’re not the answer’.

I’ve been to safari parks where I’ve seen behind the scenes the same day and seen lions that are kept in little enclosures… tiny little cement enclosures because they can’t all be put out at the same time because they’ll fight. The compromises that animals have to endure for us to see them for one hour, two hours, half a day, whatever it happens to be, two minutes sometimes.

There was an American who did a survey years and years ago in an American Zoo. He timed how long the visitors would spend in front of an enclosure watching an animal, and if the animal was asleep or not doing anything it was 2.5 minutes. And they’d move on. So, for 2.5 minutes, that animal is there for us. 2.5 minutes.

Zoos can say ‘but we contribute a lot to conservation’, I’m sorry but they don’t contribute very much to conservation and they certainly don’t return many of the animals they breed in zoos to the wild.

We’ve just got to stop interfering. Just leave it alone.

Q: How should humanity reflect on its relationship with animals?

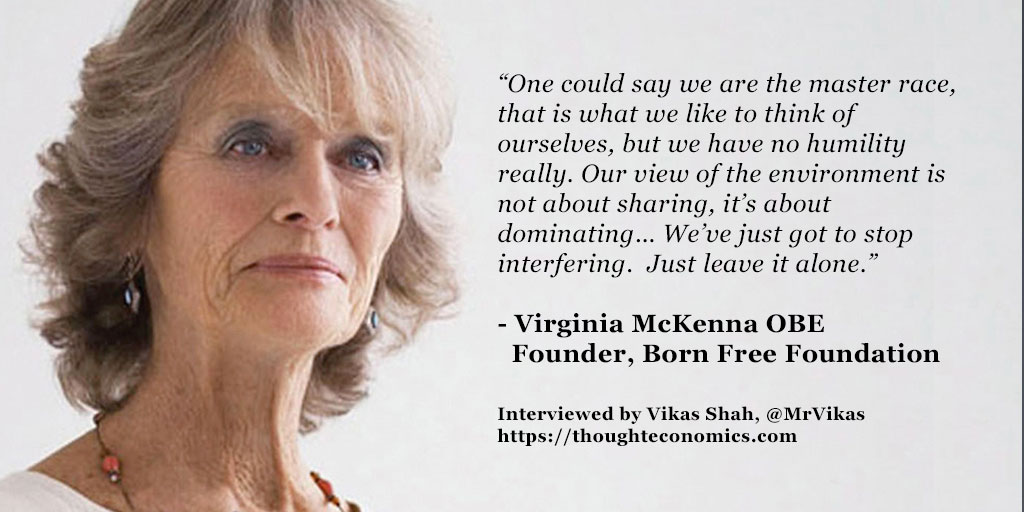

[Virginia McKenna] One could say we are the master race, that is what we like to think of ourselves, but we have no humility really. Our view of the environment is not about sharing, it’s about dominating. We want to own, we want to change, we want to knock down forests now so we can put up buildings or plant food crops. So, farewell to the creatures that call the forest home.

There’s so much at stake for our well-being, spiritual as well as physical; and it’s perhaps even more about the spiritual well-being of man. We can sit back and look at trees and we can lie under a tree and kind of look at the leaves and we are in a kind of heaven, aren’t we? Nature is so fabulous and so beautiful. And so generous. If we plant a seed, usually it grows, doesn’t it? But there won’t be any Earth to plant any seeds if we’re not careful.

[bios]Virginia McKenna OBE is Founder and Trustee of Born Free Foundation.

Following a successful career as an actress, Virginia started Zoo Check in 1984 with her late husband, Bill Travers, and eldest son, Will, after the premature death of Pole Pole, an elephant she had come to know during the filming of ‘An Elephant Called Slowly’ who was later gifted to London Zoo by the Kenya Government. Zoo Check later became the registered charity, the Born Free Foundation. Whilst Virginia still finds time to work occasionally as an actress, her leading role now is within the conservation and animal welfare movement. Virginia has also authored, co-authored and co-edited numerous books as well as travelling extensively over the years visiting zoos about which the Born Free Foundation has received complaints and, wherever possible, she accompanies rescued Big Cats to Born Free’s sanctuaries in India and South Africa. Virginia also speaks at numerous events, supports various other charitable organisations and is patron to many others.[/bios]