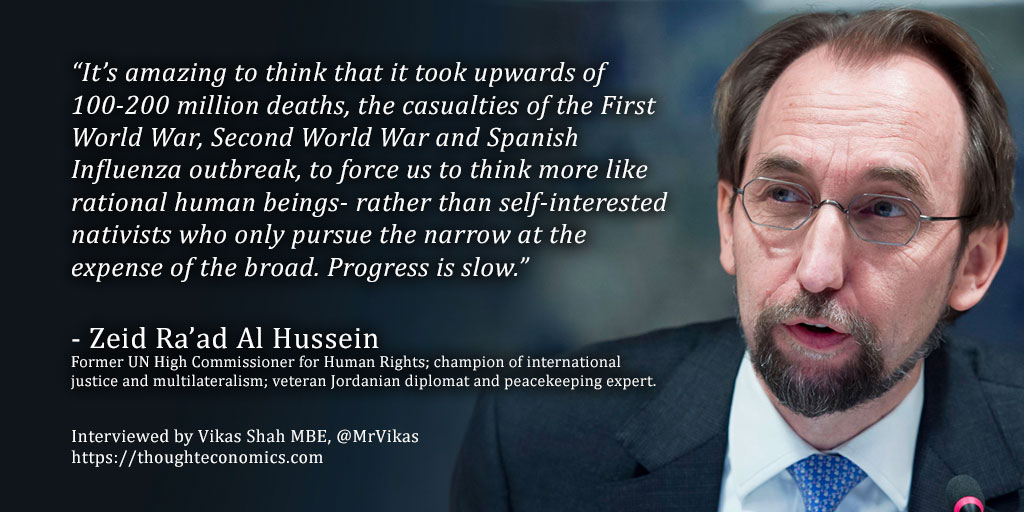

Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein has led an incredible career in diplomacy, peacebuilding and human rights. He was the UN human rights chief from 2014-2018, was awarded the Stockholm prize for human rights in 2015 and the Tulip prize in 2018. In January 2014, he served as president of the UN Security Council.

In 2002, he was elected the first president of the governing body of the International Criminal Court (ICC). He chaired some of the most complex legal negotiations associated with the court’s statute, contributed to the international community’s efforts at countering the threat of nuclear materials being trafficked by terrorists and led the UN’s efforts at eliminating sexual exploitation and abuse in UN peacekeeping.

Zeid twice served as Jordan’s ambassador to the United Nations (in New York) and once as Jordan’s ambassador to the United States. He represented Jordan twice before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). From 1994-1996, he was a UN civilian peacekeeper with UNPROFOR. He has degrees from Johns Hopkins and Cambridge universities and is currently the Perry World House Professor of the Practice of Law and Human Rights at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2019, he was appointed a member of The Elders, an independent group of global leaders working for peace, justice and human rights, founded by Nelson Mandela. Also, in 2019 he was elected an International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and awarded an honorary KCMG by HM Queen Elizabeth II, for his service to human rights.

In this exclusive interview, I spoke to Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein about human rights, the role of diplomacy in our world, and why we so urgently need the tools of diplomacy and peacebuilding in our world right now.

Q: What is diplomacy, and why do we need it?

[Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein]: Diplomacy is the management and regulation of relationships between states, but it’s also the craft by virtue of which we create treaties. Diplomacy is therefore a system from which we maintain a sense of stability, predictability and decency about how we should approach issues. Competition is almost inevitably a key issue too, but- if not kept within boundaries, through the work of diplomats can often have dire consequences.

Most diplomats are engaged in bilateral matters; the maintenance of the relationship between two governments or states. That sort of work is intensive, covers many fields, and you have to become an expert in a range of areas. Multilateral diplomacy is different, it requires you to articulate regulations and laws through treaty-making (principally) and that demands a different skillset, and that’s often where we have the weakness when it comes to maintaining international order. Only a handful of diplomats and governments are prepared to put the global good before the national interest. Seldom is it the case for any diplomat that they put the global good high up on the agenda; in my career I’ve seen it very rarely. Only 30 of the 193 or so ambassadors at the UN in NY will be devoted to a multilateral context. Most are pursuing bilateral interests in a multilateral context.

One of the key problems is therefore that too much rests on the shoulders of too few to carry the load, so when you shake the globe a little, everything falls apart- that’s what we’re seeing now with the crumbling of the international system, and hence- the international order. The UN, G20, G7… all these bodies are designed to provide a path to problem solving collectively and they’re not working… that’ symptomatic of the fact that we (as a global society) are not as committed as we seem to maintaining order in the way we have done previously.

Q: What is the role, and importance, of the international criminal courts?

[Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein]: The international criminal court (ICC) was constructed in a very clever way. The principal innovation of the court is enshrined in Article 27 of the Rome Statue which concerns the irrelevancy of official capacity. In other words; in national systems, a head of state, head of government or member of parliament is entitled to immunity from criminal prosecution. This court [the ICC] basically makes the argument that this immunity counts for nothing if the allegations waged against you involve the commission of genocide, war crimes or crimes against humanity also, the court was designed to sit in the background and the message to governments was therefore that they should do their jobs, under the terms of their constitutions and penal codes. If you (as a government) do your job, there’s no need for the International Criminal Court to intervene. The court was also designed to be independent, meaning that it could move cases itself rather than being told to do so by the Security Council or government. It’s amazing to think that it’s taken so long for a court like the ICC to exist.

Q: How can we stop leaders from breaking their responsibilities or peace and human rights?

[Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein]: In my experience, unless you are directly affected by a human rights abuse, you are unlikely to give it a second thought. How many times do you draw breath a day? It’s about 22,000 times – you don’t think about it until you can’t. Maybe you’re on a ventilator… maybe you’re being strangled… but you don’t have to think about your next breath unless you’re being strangled. That’s exactly how most people view human rights- they are generally apathetic and may express some concern or sympathy when they hear about something on the news, but they don’t mobilise unless it affects them directly.

Today’s world has very mediocre leadership. Heads of state and government do not call each other out! Putting President Trump’s own views on China to one side, you rarely- if ever- hear world leaders calling out Xi Jinping on the treatment of the Uighur people, for example.

The human race itself is also cellular, it’s not mutually reinforcing. I will ask you to help me, as I claim my rights, if I am abused and oppressed – but I need to also be prepared to help you as you are claiming yours. That doesn’t always happen. We will fight for the rights of one group (for example, we fight against the odious phenomena of violence against women), but when it comes to migrant’s rights? We take a different view.

You cannot do that. You have to be consistent across all rights. If you want your own rights to be upheld and respected? You have to be prepared to support others who discriminate against others.

Q: How can we rebuild the trust that’s needed between government and citizenry?

[Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein]: We need things to be placed on the table. We need the hypocrisy and cowardice that seems inherent in many governments to be exposed and that includes the human rights agenda. You cannot say you support a values based human rights agenda and have your defense industry dictate the terms of your relationships between states to the extent that you won’t criticize states who you sell weapons to. People see this for what it is, they recognise the internal and external inconsistencies and are tired of it. People are tired of seeing the same people suffering time and time again- the groups marginalised through austerity, the pensioners who are on the margins of economic existence and crushed by economic policy, the groups impacted by Covid-19.

People are fed-up, they see the political class becoming more and more self-serving, driven by other motives than the good of the people they represent. When you contrast that with human rights defenders, they are willing to self-sacrifice, to give everything to defend the community… not just their community, but everyone’s rights. Why can’t’ politicians be like that?

Q: Are you hopeful for the future?

[Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein]: If President Trump is re-elected, it’s going to be very difficult to emerge from our current crises. We are already in a desperate situation when it comes to climate change, and we have a looming confrontation between China and the US in particular. All these chronic and armed conflicts we see aren’t disappearing, they’re getting worse. Look in the Sahel in West Africa, it’s only a matter of time before extremists will take over the entire region. Look at what’s happening in Hong Kong, Taiwan… it feels like all the wheels are coming off the world essentially, at the same time.

If you ask me to think optimistically- the descent into utterly broken states is slower than most people would anticipate it to be, and we can predict it happening- so if we can see that society is falling apart, there is a likelihood that it may not.

Human progress often comes at great cost to people who are willing to sacrifice for the sake of principles or in defense of the rights of others. It took hundreds of millions of people to die before we created a global security and human rights order and all of these are under stress. One would hate to think it would be another similar amount of deaths before we made more progress.

Today’s Coronavirus crisis is not a force-majeure, it is a biological phenomenon, the spread of which is an indictment , and commentary on the mediocrity global leadership. It should never have escaped Wuhan, and the fact it has shows a failure fo leadership and now the very same people who are responsible for neglecting these issues are being invited to comment on it, and lead our way out. It shows how utterly messed up our world is.

What gives me hope is that there are many good people in our world, who are not politicians, who are doing the most amazing work and who- somehow- are inspired enough to overcome the huge challenges our world faces right now.